Explore options for where to give birth and understand how this decision can impact the birth experience.

Every woman and birthing parent has the right to decide where they give birth and to change their mind at any time during pregnancy or labour (NHS, 2024). It’s a personal decision, shaped by the need for clinical support, and practicalities such as location, personal preferences, and changing circumstances.

If there are concerns about a planned place of birth, a senior midwife or doctor should arrange a formal discussion, so a woman or birthing person can make their own informed decision. Healthcare professionals should not share personal views or judgements about where someone decides to give birth (NICE, 2023).

NCT Antenatal courses provide an opportunity to discuss the options and feelings around place of birth during pregnancy.

When does the decision about place of birth happen?

The decision about where to give birth can be made or changed at any time in pregnancy or during labour.

At the booking appointment (8-12 weeks) the midwife will share the local options for where to give birth. At the 34-week appointment there should be another opportunity to discuss the birth plan, including where to give birth (NHS, 2023).

What are the options for place of birth?

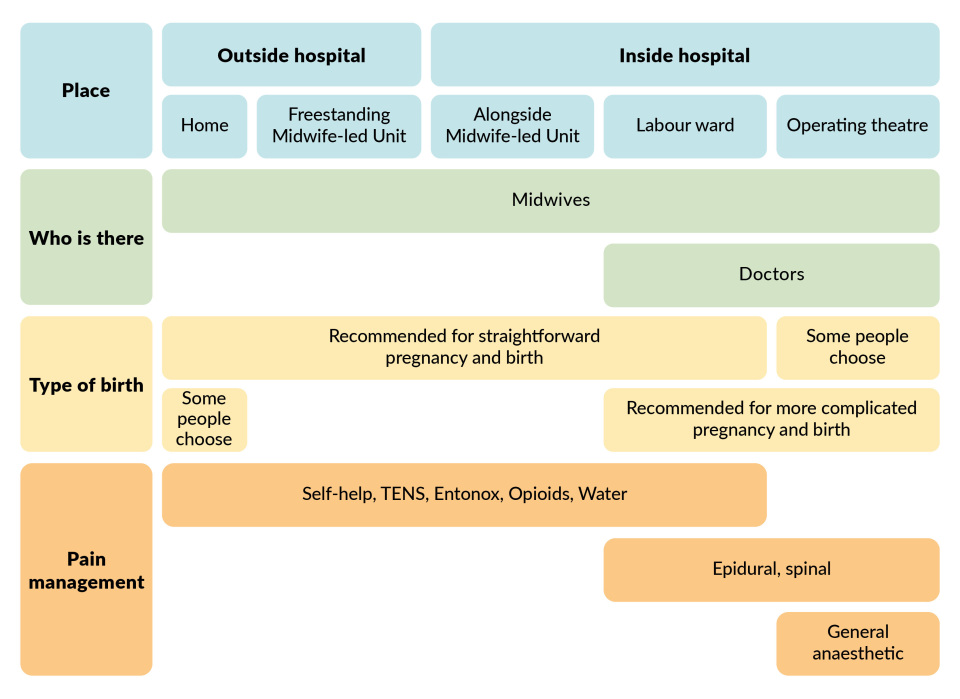

In the UK, a baby can be born at home, in a midwife-led unit (MLU), in a hospital labour ward, or a hospital operating theatre. A woman or birthing person can plan to give birth in any of these settings, where they are available (NHS, 2024).

Expectant parents do not have to choose the closest hospital or MLU (Gov.uk, 2024). Maternity services may also redirect a woman or birthing person if a unit is understaffed or too busy to accept them.

With some medical conditions it may be recommended to give birth in a hospital labour ward or operating theatre (NHS, 2024).

Home birth

In the UK, most hospital Trusts or Boards have a home birth team who support women and birthing people to give birth at home, under the care of community midwives. This option is covered in detail in our article, ‘Is home birth the right decision for me?’

Midwife-led Units (MLUs)

MLUs are also known as birth centres, midwifery units, birthing centres, birthing units, or, in Scotland, community maternity units (CMUs). They are designed to be comfortable and homely. Care is provided by midwives, not doctors. There are two types of MLUs (NHS, 2024):

- ‘Freestanding’ MLUs are separate from the hospital and are based in community settings. If clinical care is needed for the woman or birthing person, or their baby, they can be transferred to hospital by ambulance.

- ‘Alongside’ or ‘co-located’ MLUs are located on the same site as a hospital labour ward, either next door or on a different floor. If additional care is needed, a transfer to the labour ward or operating theatre will be quicker than from a freestanding MLU.

Some areas have both freestanding and alongside MLUs, others have one or none. The midwife will be able to explain what is available locally.

Hospital labour ward / obstetric unit

Women and birthing people who have a clinical need are encouraged to give birth on a hospital labour ward, where (NHS, 2024):

- Care is provided by midwives, who can call on a specialist doctor called an obstetrician [ob-ste-trish-un] if medical support is needed.

- If requested, a doctor called an anaesthetist [an-eez-the-tist] can administer epidural pain management.

- Depending on the hospital, some level of neonatal care will be available if needed.

Operating theatre

Planned caesarean births take place in a hospital operating theatre. Some hospitals have more than one operating theatre, which means planned caesarean births are not disrupted by unplanned births. Find out more about planned and unplanned caesarean births.

This graphic provides a useful summary of the key differences between different birth locations, which we explore in more detail below. All of these options can be discussed with a health professional.

Planning birth in a midwife-led unit or birth centre

In a birth centre, midwives provide care during labour, birth, and immediately after a baby is born. MLUs are smaller than labour wards and have a better ratio of staff to labouring women and birthing people. However, there are no doctors.

The labour room will cater for one labouring person. It will include a chair for a birth partner and have a private bathroom with a toilet and either a bath or shower. Some rooms may also have the ability to control the lights and temperature, and active birth tools such as a birth ball. A few may include a pool for use in labour.

Advantages of planning to give birth in a midwife-led unit (NICE, 2023; NHS, 2024)

- Surroundings that feel more relaxed.

- More likely to be cared for by a familiar midwife who has more time to focus on the labouring woman or person.

- Higher chance of spontaneous vaginal birth, without forceps or ventouse.

- Some MLUs have a birthing pool for labour and waterbirth.

- There may be other active birthing tools at the unit.

- All pain management options available, except epidural.

- Ability to adapt the birthing environment, including light and temperature.

- No difference in outcomes for babies compared with the labour ward.

What else to consider when planning birth on a midwife-led unit

- If there is concern about the wellbeing of the pregnant woman or birthing person, or their baby, then transfer to a hospital labour ward will be necessary. This will be quicker from an alongside unit than a freestanding unit.

- After the birth, discharge to go home will be within a few hours if all is well.

- Some MLUs offer additional support with breastfeeding after birth.

- It is important to check if this option is supported by the healthcare team for your individual circumstances.

Planning a birth on a hospital labour ward

Hospital labour wards are also known as obstetric units. They provide care for women and birthing people who have additional clinical needs, or who want to be closer to medical support for themselves or their baby.

On the labour ward most care is carried out by midwives. If needed, the midwife can consult with a doctor. Labour wards tend to be busier than MLUs, and the midwife is likely to be caring for other people at the same time.

Facilities vary between hospitals, so it can help to arrange a physical or virtual tour or speak with a midwife in advance.

The labour room is for one labouring person, and includes a chair for a birth partner and a private bathroom with a toilet and either a bath or shower. Some may also have controls for the lights and temperature, and active birth tools such as a birth ball. A few may include a pool for use in labour.

Advantages of planning birth on a labour ward

- Pain management includes all options available at home or in a MLU, plus anaesthetists are available for an epidural.

- Access to obstetricians if pregnancy is, or labour becomes, complicated.

- Access to specialists in newborn care (neonatologists) and a special care baby unit if a baby or babies need additional medical support.

(NHS, 2024)

What else to consider when planning a labour ward birth

- Care is more likely to be provided by a different midwife than during pregnancy, and the midwife is likely to be caring for other people at the same time.

- Doctors and other healthcare professionals will only attend if needed.

- Compared with home or MLU, planning birth in an obstetric unit is associated with a higher chance of vaginal birth with forceps or ventouse, episiotomy or unplanned caesarean birth.

- There is no difference in outcomes for babies compared with MLUs when the pregnancy is low-risk.

- After the baby is born, new parents and their baby may be discharged from the labour ward to home. If further medical support is needed they are moved to the postnatal ward for a period of recovery.

- It is important to check if this the option is recommended by the healthcare team for your individual circumstances.

(NHS, 2024; NICE, 2023)

What happens if circumstances change during labour and a woman or birthing decides to transfer?

Most women and birthing people give birth in the place they had planned. However, during labour, midwives are always thinking ahead to anticipate and avoid any issues that may arise.

Sometimes a woman or birthing person who had planned to give birth elsewhere will transfer to hospital after labour has started. Some transfers are made before the baby is born and some after. Like any other decision in pregnancy and birth, the woman or birthing person can accept or decline any suggestion at any time.

Transfers are for assessment before a decision, rather than immediate action. They are most commonly the result of labour slowing down. This accounts for around 35 in 100 women or birthing people transferred from home or MLUs (NICE, 2023).

Other reasons include:

- concerns about the baby’s heart rate (7-10 in 100)

- requests for pain management (5-13 in 100)

- repairing a perineal tear (7-10 in 100)

- neonatal support for a newborn baby (1-5 in 100)

(NICE, 2023)

In a straightforward, low-risk pregnancy, the chance of transfer is higher for a first birth (NPEU, no date):

| First birth | Second or subsequent birth | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planned place of birth | Remain there for birth | Transfer to Labour ward for assessment or further care | Remain there for birth | Transfer to Labour ward for assessment or further care |

| Home | 55 in 100 | 45 in 100 | 88 in 100 | 12 in 100 |

| Freestanding MLU | 64 in 100 | 36 in 100 | 91 in 100 | 9 in 100 |

| Alongside MLU | 60 in 100 | 40 in 100 | 87 in 100 | 13 in 100 |

The same pattern is seen in more complicated pregnancies (NPEU, no date):

| Planned place of birth | Remain at home or MLU for birth | Transfer to Labour ward for assessment or further care |

|---|---|---|

| First pregnancy | 44-54 in 100 | 46-56 in 100 |

| Second or subsequent pregnancy | 77-82 in 100 | 18-23 in 100 |

Depending on the location and circumstances, a woman or birthing person may travel by car or ambulance. It’s a good idea to discuss transport with the midwife in advance. Remember to consider how birth partners will travel too.

How to decide where to plan birth

Many expectant parents will use a birth plan to help discuss where they want to give birth.

Evidence shows that for women and birthing people with straightforward pregnancies, there are no differences in outcomes for the baby in MLU or labour ward (NICE, 2023).

For a first birth and a straightforward pregnancy, the chances are (NICE, 2023):

| Planned place of birth | Straightforward vaginal birth | Birth with forceps or ventouse or caesarean |

|---|---|---|

| Home | 794 in 1000 | 206 in 1000 |

| Freestanding MLU | 813 in 1000 | 187 in 1000 |

| Alongside MLU | 765 in 1000 | 235 in 1000 |

| Labour ward | 688 in 1000 | 312 in 1000 |

For a second or subsequent birth and a straightforward pregnancy, the chances are (NICE, 2023):

| Planned place of birth | Straightforward vaginal birth | Birth with forceps or ventouse or caesarean |

|---|---|---|

| Home | 984 in 1000 | 16 in 1000 |

| Freestanding MLU | 980 in 1000 | 20 in 1000 |

| Alongside MLU | 967 in 1000 | 33 in 1000 |

| Labour ward | 927 in 1000 | 73 in 1000 |

For women and birthing people with more complicated pregnancies, evidence shows the chance of spontaneous vaginal birth is higher when giving birth at home. The research has not been done on MLUs. The chance of the baby being admitted to a neonatal unit is also lower at home for this group when planned birth is at home (NPEU, 2015).

Questions to ask when planning where to give birth

Here are some questions to consider if planning to have a baby or babies at home, in a midwife-led unit or on a labour ward (NHS, 2024):

- Are there any medical factors which affect the plan?

- Are there any personal circumstances which inform the plan?

- Is there a history of fast birth for the pregnant woman or birthing person?

- How close / accessible is it from home?

- Are tours available?

- What is the average /minimum staffing ratio? Is it a busy unit? How are shift and handovers handled?

- What is the staffing ratio during labour?

- What equipment/facilities are available?

- Does the space feel comfortable and safe?

- Is labouring in water or water birth available?

- What are the rates of induction, assisted birth, caesarean birth?

- What is the policy on birth partners during labour? What about visitors after the baby is born?

- Will I be supported to move around in labour and find my own position for the birth?

- What types of pain management are available?

- How soon will I be encouraged to go home after the birth?

- What services are provided for premature or sick babies?

- Is infant feeding support available?

- How long does transfer from home or a birth centre take? Would a midwife be with me all the time?

- What is the number for the triage line / labour line to call for support in labour?

Further information

Birthrights has a factsheet on legal rights around place of birth.

NHS England has a visual guide on the benefits and drawbacks of each location.

Which? provides a comparison of NHS maternity services with private maternity care.

Need more information?

For further information, we offer NCT antenatal courses which are a great way to prepare for pregnancy, birth, and life with a new baby.

Our NCT support line also offers practical and emotional support with feeding your baby and general enquiries for parents, members and volunteers: 0300 330 0700.

Gov.uk (2024) NHS Choice Framework - what choices are available to you in your NHS care. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-nhs-choice-framework/the… [24 Oct 25]

NHS (2023) Your antenatal appointments. https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/your-pregnancy-care/your-antenatal-appoint… [14 Oct 25]

NHS (2024) Where to give birth: the options. https://www.nhs.uk/pregnancy/labour-and-birth/preparing-for-the-birth/w… [14 Oct 25]

NICE (2023) Intrapartum Care [NG235]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng235 [14 Oct 25]

NPEU (2015) Birthplace in England Research Programme: further analyses to enhance policy and service delivery decision-making for planned place of birth. Study 5: The characteristics and management of 'higher risk' women in non-OU settings. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/birthplace/birthplace-follow-on-study [24 Oct 25]

NPEU (no date) Birthplace in England Research Programme. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/birthplace [23 Oct 25]